Everywhere the voices of people saying in a doubtful tone, “But it didn’t use to be like this, did it?”

And others saying with scorn, “Don’t give me that shit about the Good Old Days!” – John Brunner, The Sheep Look Up, 342

I’ve written before about the tremendously dark effect that reading John Brunner’s 1972 novel about the human suffering caused by overwhelming environmental crises had on my thinking, but this week, as I made my way through journalist Mark Hertsgaard’s book Hot, I ‘m back to the emotions that reading Brunner brought upon me. Hertsgaard’s been reporting on climate for years, but this new book was explicitly framed as a way to deal with his realization that his five-year-old daughter, Chiara, was inevitably going to live in a world changed by climate chaos. This book is worth reading, if only to batter (again!) through the walls of denial that anybody hoping to remain sane has erected against the increasingly dark truth of oncoming climate change. But in the context of this blog and my academic work, I’m particularly interested in the way that Hertsgaard used Chiara, and other children, as a way to think through the implications of climate change. “The future is not going to be like the past,” says a scientist Hertsgaard interviews. “It’s human nature to assume it will be, but with climate change that’s no longer true.”

Hertsgaard’s been reporting on climate for years, but this new book was explicitly framed as a way to deal with his realization that his five-year-old daughter, Chiara, was inevitably going to live in a world changed by climate chaos. This book is worth reading, if only to batter (again!) through the walls of denial that anybody hoping to remain sane has erected against the increasingly dark truth of oncoming climate change. But in the context of this blog and my academic work, I’m particularly interested in the way that Hertsgaard used Chiara, and other children, as a way to think through the implications of climate change. “The future is not going to be like the past,” says a scientist Hertsgaard interviews. “It’s human nature to assume it will be, but with climate change that’s no longer true.”

So. What will it be like to grow up as part of Generation Hot? For one thing, as those who left their homes in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina could attest, the places you love may be lost to you. Hertsgaard writes that his hometown in Northern California may no longer be inhabitable by the time Chiara grows up, due to rising sea levels obscuring key roadways. Hertsgaard writes, “In her mind, Chiara will always be able to revisit the place where she grew up. But at some point it may become impossible to visit here in person, at least by automobile.” This hardship pales in comparison to the lot of the Bangladeshi child named Uma who Hertsgaard invokes as another member of Chiara’s “Generation Hot”. Uma’s village is surrounded by farmland that has become so saline, because of rising sea levels, that it’s almost impossible to farm.

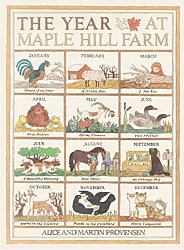

Comparing Chiara’s situation to Uma’s universalizes the human drive to feel a connection with the first landscape you knew. As a child, I loved the book The Year at Maple Hill Farm, by Alice and Martin Provensen (1978).  Looking back now, it’s clear that I liked this simple narrative, about the passage of changing seasons on a farm in upstate New York, because it reminded me of my grandparents’ farm in New Hampshire, where my family ate asparagus out of the garden in the spring, picked wild blackberries in the summer, chopped fireplace wood in the fall, and skiied through Christmas trees in the winter. The book reinforced my sense of the rightness and continuity of this particular way of climate. Even now, rifling through its pages reinforces me in the belief that the Northeast is the best, most cozy, most right place in the world. The idea that my nieces, now babies living in Maine, might in middle age find the book to be a relic of previous times, full of plants and animals that their land no longer supports, is nothing less than heartbreaking. Is this heartbreak an effect tool in climate activism? And is this really sadness on my nieces’ behalf, or am I projecting my attachment to my own childhood onto their futures? If it’s the latter, does that make a difference, or am I splitting ethical hairs here?

Looking back now, it’s clear that I liked this simple narrative, about the passage of changing seasons on a farm in upstate New York, because it reminded me of my grandparents’ farm in New Hampshire, where my family ate asparagus out of the garden in the spring, picked wild blackberries in the summer, chopped fireplace wood in the fall, and skiied through Christmas trees in the winter. The book reinforced my sense of the rightness and continuity of this particular way of climate. Even now, rifling through its pages reinforces me in the belief that the Northeast is the best, most cozy, most right place in the world. The idea that my nieces, now babies living in Maine, might in middle age find the book to be a relic of previous times, full of plants and animals that their land no longer supports, is nothing less than heartbreaking. Is this heartbreak an effect tool in climate activism? And is this really sadness on my nieces’ behalf, or am I projecting my attachment to my own childhood onto their futures? If it’s the latter, does that make a difference, or am I splitting ethical hairs here?

Forget the emotional wreck of broken ties to land. What about declining physical well-being? Hertsgaard argues that even people living in “developed” countries may face some of the same problems that the characters in Brunner’s tale did: disruptions in food supplies, lack of water, human misery intensified by global instability. Will we become like those in Brunner’s story, who suffer from asthma from air pollution (already happening to kids in cities across the US), diseases from corrupted water supplies, lack of medical care for anybody who’s not rich (also already happening)? A German physicist Hertsgaard interviews says that he fears his young son’s life will decline in quality by its end:

“It breaks my heart even to think about it…By 2080, Zoltan will be in his seventies, and he could lead a very miserable end of his life. It must be very unpleasant to be old and fragile without a functioning society around you. Today, if I have a medical problem, it is taken care of. But if our generation does not reinvent industrial society, then my son, and your daughter as well, will have a terrible end of life.”

Politicians are fond of using “the children” as a catch-all rhetorical device meant to support whatever initiative they’re pushing. (Right now, the “do it for the future” cause is “deficit reduction,” which of course leads straight to cutting social services that help today’s poor children—a fact that makes it clear exactly whose children we’re “doing it for”.) Will making people think about their children’s quality-of-life as forty-year-olds, or seventy-year-olds, spur them to make environmental changes that they wouldn’t have made otherwise? What could be the key argument to move people when picturing their children’s future: loss of ecosystem continuity, health, disruption?

Hertsgaard’s book is mostly about the adaptations that some communities are making in order to face the oncoming changes—he argues that since we’ve already hit the point of no return, and the climate is definitely going to change, we should start building infrastructure that can survive sea level rise, communities that are closer together so we’ll be able to walk places when we lose easy access to oil, etc. Reading his book made me realize, yet again, that one of the greatest obstacles to enacting these changes is the emotions you have to swallow in order to get to a state of mind that favors action. Many smart people deny climate change (as this post argues) not because they don’t know about it, but because they refuse to believe it. Will invoking The Children or The Future reverse that refusal, or strengthen it?