“Dear future generations: Please accept our apologies. We were rolling drunk on petroleum. – 2006” – Kurt Vonnegut, from his Confetti project

Last month, Sara Reardon’s research, “Climate Change Sparks Battles in the Classroom,” based on interviews with 800 members of the National Earth Science Teachers Association, reported that “climate change was second only to evolution in triggering protests from parents and school administrators.” I read this finding while I was immersed in Saci Lloyd’s three YA books about climate change and energy troubles, The Carbon Diaries 2015, The Carbon Diaries 2017, and Momentum. As I’ve mentioned on this blog before, I’m in the very preliminary stages of research for a new project on the ways that American environmentalists have used “future generations” as an argument for acting to forestall environmental disaster; I’m also very interested in the ways that we tell these “future generations” about the problems we’ve caused, and whether, and when, these narratives amount to apologies. To me, Lloyd’s books feel like something sui generis: YA science fiction that addresses these issues of intergenerational environmental justice head-on.

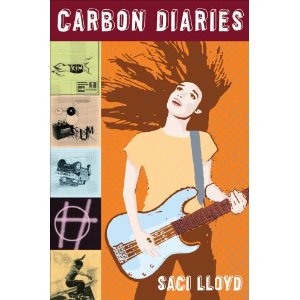

Saci Lloyd is a high school teacher in London, as this great Guardian interview describes in length, and although media studies, not science, is her area of expertise, she’s written three novels that do much to bring home the day-to-day realities of a near future marked by energy scarcity and climate change. Lloyd’s books, which feature a scrappy heroine facing hardship in a harsh landscape, may seem at first glance to operate in the mode of other recent YA successes like The Hunger Games—and, indeed, they’ve provoked interest from filmmakers, just as Suzanne Collins’ more famous series did (the Carbon Diaries will be filmed by Company Pictures for the BBC, says the Guardian). But unlike the Hunger Games trilogy, the two Carbon Diaries books are of the “Soft Apocalypse” genre. Books that take this approach chronicle societies changing as a result of a series of rolling crises, rather than in the blink of an eye, as from a nuclear blast or a zombie outbreak. In the “soft apocalypse,” as Scott Timberg wrote on io9 recently, “the end has come but life goes on”: bad things may happen, but people still try to form communities and shape new ways of life. Examples would be Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, James Howard Kuntsler’s World Made By Hand (which I reviewed here), or Will McIntosh’s pithily-named Soft Apocalypse. Because they take this “soft” approach, Lloyd’s Carbon Diaries books are wonderful at showing the effects of climate change and scarcity on everyday life; they’re also completely terrifying.

The first Carbon Diaries opens with our narrator, Laura Brown, a sixteen-year-old Londoner, describing the institution of carbon rationing in the UK. The system is harsh—each citizen gets a ration card, which they can use to activate appliances in their home, take the bus, or buy airplane tickets, though flying has become so “expensive” in terms of carbon that nobody does it. Although reviews of the Carbon Diaries note that Laura’s diary contains a fair dollop of “normal” teenage life—she’s in a band, she has a crush on a boy at school—the best parts of the book, so far as I’m concerned, have to do with the way that carbon rationing changes these human relationships. In Laura’s family, rationing upsets the precarious peace that formerly reigned in a household made up of two willful teenage girls and two slightly mismatched parents. Laura’s sister, the spoiled Kim, hides in her room, listening to music and taking scalding-hot showers, until the government realizes how much carbon she’s burning and enrolls her in a “carbon offenders” training program. Laura’s dad tries, in a fumbling way, to adjust to the new order, and plants a large backyard garden, even going so far as to buy a pig; her mother goes through a period of denial, and her parents’ marriage comes close to splitting up. Romantic relationships change, too. Laura’s crush, Ravi, sees his dating stock shoot up at school, because he’s good at retrofitting appliances to use less electricity; the family’s next-door neighbor, Kieran, starts a company called Carbon Dating, which is meant to help single people readjust to a world in which conspicuous consumption can’t grease the wheels of human interaction. The books slide close to utopic dreaming occasionally, as when Laura’s block comes together to bust the black marketeers who are selling carbon points and driving around in gas-guzzling Hummers, but the book doesn’t try to convince you that a post-oil life will be kind of all right by arguing that community togetherness will replace all of the material comforts we previously knew and loved. That’s because Lloyd does a good job of showing how lack of oil, and scanty power, might coincide with rapid and scary climate shifts, which will put paid to citizens’ attempts to provide for themselves by planting gardens and huddling together to get through the winter. Laura’s dad’s garden, for example, shrivels up and dies when the government begins water rationing partway through The Carbon Diaries 2015, and the pig, symbol of the Browns’ new world as urban peasants, gets swept away by catastrophic flooding. (Vermont, I’m thinking of you.)

The Carbon Diaries series found a US publisher, Holiday House; I wonder whether it’s getting assigned in English classes here, or whether American teenagers are reading it. If we can’t talk about climate change in science class, maybe we can do it elsewhere.