Book

Since World War II, our conversations about children and scientific vocation have been wistful and nostalgic. The conversational trope “Children just don’t love science like they used to” conjures an imagined past, full of the joy of experimentation and discovery. Although some experts now argue that we no longer actually face a scientific “manpower shortage,” popular belief in the concept has proven durable.

Why do we love this idea so much? What other cultural beliefs—about gender, selfhood, and citizenship—does it reinforce?

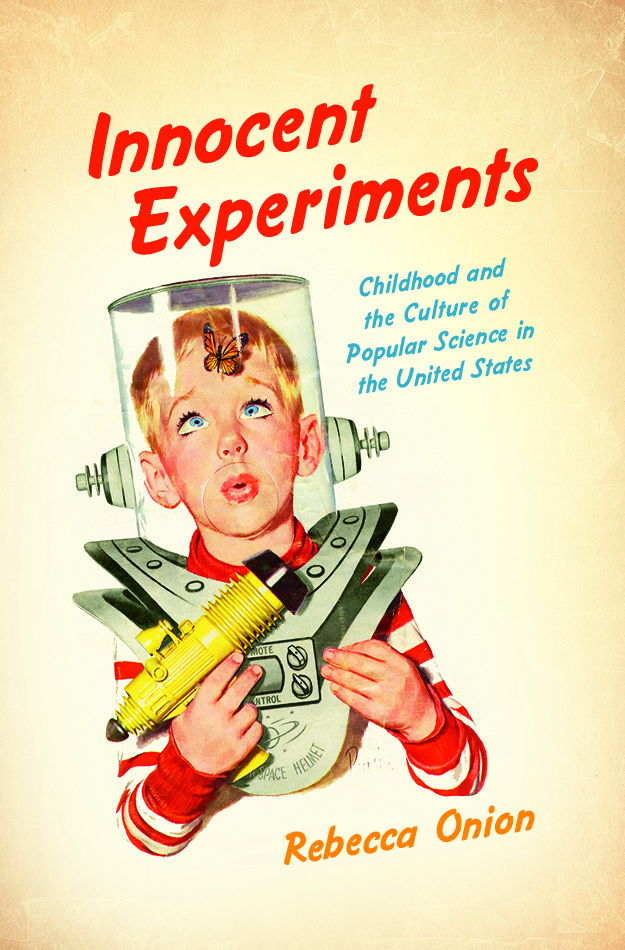

My first book, Innocent Experiments: Childhood and the Culture of Popular Science in the United States, published by the University of North Carolina Press in the fall of 2016, looks at twentieth-century efforts to promote science in American children’s lives, and asks how these projects reflect American culture’s awkward reconciliation with science. The book tackles issues of unequal representation in STEM fields from a cultural angle, showing how the dominant emotional modes of idealized childhood science practice—understood as curiosity, individualism, and originality—have been coded as male.

Here’s some coverage of the book:

- Interview with the podcast Lady Science, December 2019

- Review by Deanna Day in the Journal of American History, September 2018

- Review by Sevan Terzian in History of Education Quarterly, August 2017

- Interview with Lisa Hix of Collectors’ Weekly, August 2017

- Review by C.H. Wixon in CHOICE, May 2017

- Interview with Laura Ansley for Nursing Clio, December 2016

- Review by Kacey Sease for Nursing Clio, December 2016

- Review by Rachel Riederer for The New Republic, December 2016