For the past two weeks, I’ve been at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia, benefitting from their travel grant program, which is supporting my research in their large collection of chemistry sets and other science sets. Before I came here, I thought I would be able to use these sets and their accompanying manuals to answer a couple of questions: What did manufacturers think kids would be doing with these sets? What types of kids (gender, race, age) did they assume would buy their products? What were the companies’ marketing techniques? How did the manufacturers try to differentiate themselves one from the other? How did the sets change over time? How programmatic were the experiments the manufacturers proposed? And would there be any evidence of the way kids actually used the sets? (Miriam Forman-Brunell, in her book on dolls, did an analysis of wear patterns to make an argument about the way girls might actually have used these objects; I thought maybe I could do something similar with these sets.)

I knew before I came here that the art associated with these sets would blow my mind; the CHF has a wonderful set of photographs of the front-of-the-box art on Flickr that I’ve been using to shape my preliminary analysis. I’ve said before that I think I chose my dissertation topic based partially on the eye appeal of the primary sources, and these sets prove my point. Now what I need to do is find a way to discuss the visuality of these sets in a more academic way—but maybe not in this blog post, which is all about looking at pictures.

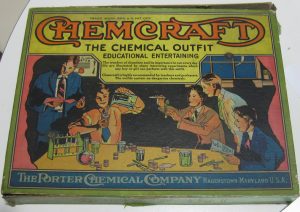

Here’s one of the older sets, featuring a group of boys in a magical nighttime laboratory, moon and stars looking on while be-tied and be-jacketed lads experience the Joy of Knowledge. As with all of these images, I suggest you click to enlarge:

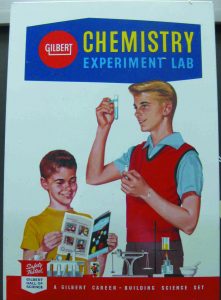

The newer sets tend to have a cleaner, more modern appeal, and the boys graduate from ties to sweater vests. The onlooking younger sibling (often a girl, though not in this particular image) is a common feature in these representations:

“Gilbert Chemistry Experiment Lab.” The A. C. Gilbert Company, New Haven, CT, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, 2005.121.

Most of the sets have accompanying manuals, which are like mini-textbooks, often introducing the reader to the technical and social aspects of the science behind the toy, before moving into suggestions for experiments. The manuals are just as attractive as the sets. (And yes, these toy companies suggested that kids should create their own lab equipment via a little amateur in-home glass-blowing.)

Porter, Harold M., ed. Chemcraft Spectroscope Experiments: Observing the Colorful Spectrum of Light. Hagerstown, MD: The Porter Chemical Company, 1937.

Lynde, Carleton J. Gilbert Experimental Glass Blowing for Boys. Edited by A. C. Gilbert. New Haven, CT: A.C. Gilbert Company, 1909.

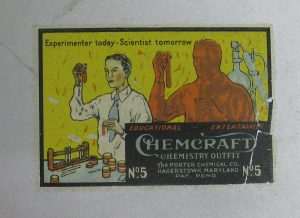

Many of the Chemcraft sets featured this label, about two inches by one, on the lower right-hand corner of an otherwise solid-colored case.

“Chemcraft Chemistry Outfit.” The Porter Chemical Company, Hagerstown, MD, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, 2005.043.

The stuff inside the boxes is equally attractive. Take, for example, this atomic energy section in a later chem lab:

“Chemcraft Senior Laboratory No. 415.” The Porter Chemical Company, Hagerstown, MD, ca 1950. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, GB98:09.002.

I even found myself swooning over those little illustrated cardboard spacers between the carefully labeled chemical canisters:

“Gilbert Chemistry Outfit.” The A. C. Gilbert Company, New Haven, CT, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, GB98:09.001.

And how about this “chemical rocket,” an insert in an undated, but clearly space-age-era set? If I were in the market for a tattoo, I would happily get this inked on my leg, like this guy did with the Saturn V.

“Lionel-Porter Chemcraft Chemistry Lab.” The Porter Chemical Company, Hagerstown, MD, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, 2005.079.

Before I opened up the first box of sets, Rosie Cook, the CHF collections staffer who’s helping me with my visit, asked me if I wanted latex gloves, because some of the chemicals had gotten loose. And indeed, some of the sets were in better shape than others.

“MidgetLab Chemical Outfit No. 1.” MidgetLab Company, St. Louis, MO, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, GB98:09.007.

But I only really wanted those latex gloves when I ran across this set, which contained mummified pond creatures from long ago:

“Lionel-Porter Biocraft Biology Lab,” n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, 2006.069.031.

Here, by the way, is the original advertisement for the Biocraft set, in which the marine life looked a bit more lively. I wonder if today’s science toy companies would ever market an at-home dissection kit featuring formaldefishies? That’s some research I need to do.

“Porter Science Catalog,” 1961. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, GB98:09.054, Chemistry Set Paper Ephemera.

Although the publication date is a bit out of my chronological range, I liked the authorial voice in the Mr. Wizard chemistry set manual—host Don Herbert, pictured below, placed himself in the kids’ shoes and honestly admitted a lack of expertise.

Herbert’s kit was also the only one I saw to feature a Mystery Powder, which kids were supposed to use their newfound chemical knowledge to identify:

Some of the pages in the Mr. Wizard manual were unintentionally funny (sorry, the upcoming is mildly immature, but archives make me a bit giddy):

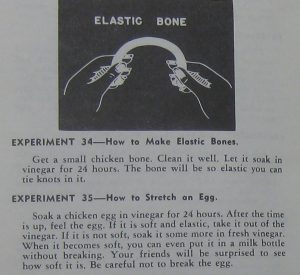

Back on the straight and narrow. What about the experiments these books suggested? Here are a couple I’d like to try out, perhaps for a later post. First, the chicken bone and elastic egg. Variations on these experiments appeared in almost every manual, across the chronological spectrum. Has anybody tried either of these, and do they work?

What about this “weather doll,” which also appeared over and over again? Her skirt changes colors along with the air’s humidity:

Porter, Harold M. “Porter Chemcraft Junior Experiment Manual.” The Porter Chemical Company, Hagerstown, MD, 1956. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, GB98:09.004.

Finally, I’ll be talking a lot about the way that these manuals address the technologies of war—first, after WWI, the use of chemical gas, and second, after WWII, the atomic bomb. Here’s a bit about phosphorus that made me wonder: is the manual suggesting that kids actually experiment with their own guinea pigs, or is that last paragraph just informational?

Johnson, Treat, and A. C Gilbert. Fun with Gilbert Chemistry. The A. C. Gilbert Company, New Haven, CT, 1946. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, GB98:09.007.

Back to the question I posed above about how the kids used the sets. Here and there, I spotted scribbles on the manuals and sets, like the doodles one owner made on the cover of this microscope set manual:

“Microset Instructions for Model No. 2MX.” Carolyn Manufacturing Co., Inc., n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, 2006.069.001.

One owner wrote the date of his receipt of the set right on the set itself (this reminds me of something I would have done at a certain property-loving age):

“Microcraft #60.” The Newman-Stern Co., Cleveland, OH, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections.

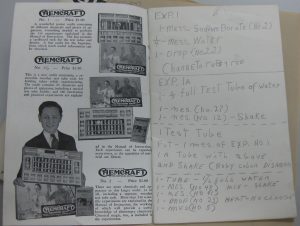

A “laboratory notebook” from one set had a bunch of careful notes on the first page, but the rest of the pages were completely empty:

“Chemcraft Chemistry Outfit Note Book.” The Porter Chemical Company, Hagerstown, MD, n.d. Chemical Heritage Foundation, Object Collections, 2005.043.

One chemistry book featured a cryptic inscription from Mom and Dad (was this gift a reward or a guilt trip?):

None of these scribbles enlightened me very much about the way kids might have taken these Christmas gifts and used them—for good or ill. I spoke with an older family friend recently about his own experience setting up a chemistry lab in his bedroom in the 1940s. This friend, who eventually became a scientist, said that he told his parents nothing about what he was doing in his room, because they wouldn’t understand; he also said he didn’t bring any of his friends in on the fun, because he didn’t want to hurt them if his experiments blew up in his face (which they sometimes did). This was totally contrary to the image of the camaraderie-filled “science club” that many of these kits perpetuate (see the first picture in this post for an example). This conversation led me to believe that perhaps I need to do some oral histories. Is there anyone out there who grew up in the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s and used chemistry sets? Send me an email—I’d love to hear from you.

Next week: The Problem of Dinosaurs.

Bridger

Oct 15, 2010 -

Oh, I love this, love this, love this. The egg in vinegar works — I think it’s the secret to getting the suck-an-egg-into-a-wine-bottle trick to work (the one that failed at that fateful NH-NYE of yore). And I have a zillion relatives who played with 1940s and 1950s chemistry sets. Let’s talk tomorrow night!

rebecca

Oct 15, 2010 -

Oh yes!!! I forgot about that wine-bottle thing we tried to do…I knew it was a dim memory from somewhere, but couldn’t pinpoint. This year I’ll bring the instructions. And yes! let’s talk tomorrow.

Katie

Oct 15, 2010 -

Great post! I love the set of detailed notes that someone left on just the first page. The mini “writer” me from childhood would have enthusiastically started that kind of note taking and then totally forgotten about it after a day or two. Ah, fickle youth.

Also, my dad did some “experiments” with the speed at which Easter grass burned in his closet as a boy. Similar hiding science/hiding recklessness story.

rebecca

Oct 15, 2010 -

Ha! I bet Easter grass burned at a scientifically measured speed of “mighty fast,” and produced a “really bad” smell. I’m definitely going to be talking about explosions and smells in this chapter, that’s for sure.

Katie

Oct 15, 2010 -

No, worse! He set his parent’s whole bedroom on fire. It was pretty bad. Easter grass was mylar back in the day.