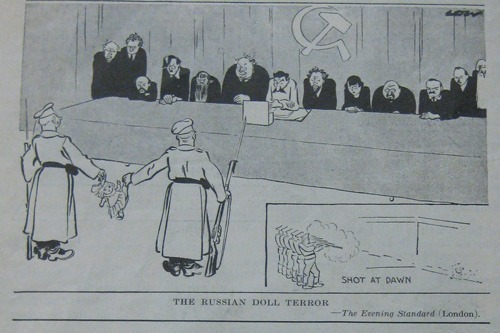

Just a short post today about a couple of intriguing (and disturbing) cartoons I’ve found via recent periodicals research. First up, from The Literary Digest of 1930 (originally published in the London Evening Standard): “The Russian Doll Terror,” in which a commission of dour Russian bureaucrats with poor posture pass judgment on an innocent dolly; the inset of the cartoon shows that same dolly in front of a firing squad. The text of the accompanying article reads: “Great excitement has been stirred up in Moscow, it seems, because of the discovery by a loyal Bolshevik that the toys of Russian children corrupt their minds.”

According to the story, a “Mr. D. Popov” proposed in a Moscow newspaper that the Commissariat of Education should create a commission to vet toys. What kinds of toys was Popov crusading against? The list reads like a rundown of playthings that later generations of American liberals would call into question. Viz: Little-mommy miniatures for girls:

He first of all attacks such toys as miniature oil-stoves, household dishes, etc., on the idea that such toys would merely make the child “a good candidate for the title of ‘wife and mother’ in the bourgeois-patriarchal sense of these words.”

And dolls that caricature black people:

Mr. Popov writes…”Negro-dolls are made out idiots with faces which inspire revulsion.”

Some of “Mr. Popov”‘s objections to toys reflected the Russian mission of serious technical and scientific education for young people.*

Mr. Popov continues…”Instead of carriages and phaetons we need toys which reflect our technical revolution: cranes, machines, tractors, motorcycles, automats.”**

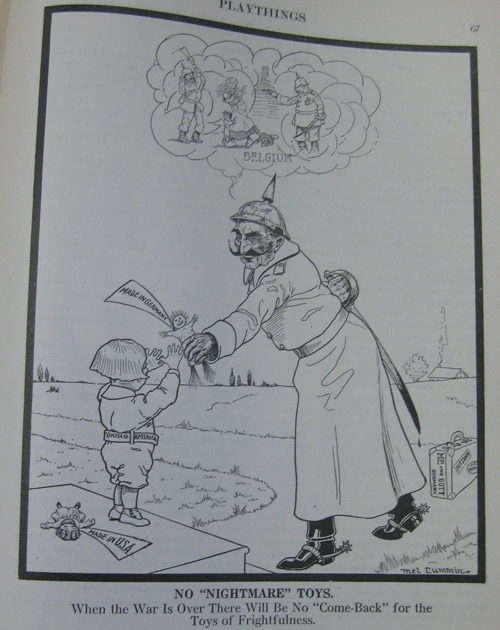

In this article, the doll is used as a stand-in for an innocent harmlessness that a repressive, humorless state is taking way too seriously. Meanwhile, twelve years earlier, in the toy industry publication Playthings, American toymakers tried to get buyers to take German toys more seriously:

Toymakers in the United States took the events of World War One as a great chance to counter the German dominance of toy markets, and in this cartoon, they invest the German toy with a malevolent past, depicting it as a “nightmare” invader carrying the dead Belgian children in its very stuffing. During this same time, Playthings also ran an approving story about a young girl in San Francisco who drowned all of her dolls in a fountain, because they were German (“Little Mother Drowns German Dolls: Sadly, But With Her Duty Plain, Takes Play Babies to Fountain and Drowns Them,” Playthings, July 1918, p. 54).

Dolls, like childhood, are both meaningless (“it’s just a toy”; “it’s just for fun”) and totally meaningful.

*Julia Mickenberg had a great essay in American Quarterly last year that recounts some of the history of Russian efforts in technical education during this time, and points out that modernity-minded, liberal/radical/progressive American observers admired the level of commitment Russia showed to educating children about science, technology, and industry. (Full disclosure: Julia is one of my dissertation advisors.)

**Given that this article was published in 1930, I’m left with a lot of questions about the actual toy landscape for Russian children at the time. If they were getting imported toys from the United States, that would explain the minstrelsy dolls, but the US toy industry was also producing a ton of Erector sets and other construction toys that would have more than fulfilled the need for toys that would “reflect…technical revolution.” Perhaps the minstrelsy dolls came from a non-US source?