The photos in this post are official American Museum of Natural History documentation of some of the projects kids brought to the Museum’s Children’s Fair, which the AMNH ran along with the American Institute of the City of New York. The first Fair at the AMNH happened in 1928; these photos are all from the period between 1930 and 1932. I love these pictures because they capture something that’s ephemeral—science projects long since junked or otherwise lost to history—but that obviously mattered very much to the young presenters at the time. They’re also a great way to see what counted as “science” in these kids’ lives. In the future I’d love to do a comparative study between these projects and the ones submitted to the National Science Fair in the forties and fifties…but that’s back-burner for now.

(All photographs are used courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History. The AMNH has fun online photo archives to browse; you can see those at this link.)

"The Children's Fair," "Allen", December 1932. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 314086; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

This overhead view of the scene in the Museum’s Education Hall shows the booths housing the exhibits, the flow of traffic, and the excited faces of the young attendees. In 1928 the American Institute’s press release for the event advertised total prizes of $2,758; although the fair at first asked for projects advancing “agriculture, conservation, and nature study,” a fair number of projects tackled topics related to more modern or technical areas of interest, such as electricity and radio.

"The Story of Transportation," Julius Kirschner, December 1931. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 313803; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

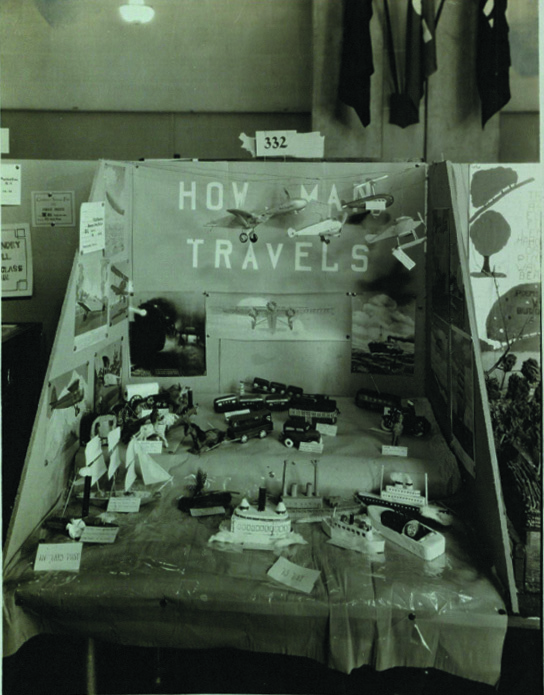

"How Man Travels," "Allen," December 1932. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 314084; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

During the 1920s and 1930s, many kids’ books focused on the workings of transportation technologies (see: Neil Harris, Planes, Trains, and Automobiles: The Transportation Revolution in Children’s Picture Books, 1995). The two images above are like material manifestations of these popular books, re-made through childish labor. I may refer to these photographs in my chapter on representations of the city and the country in science books of the 20s and 30s; they seem like a good way to see how these books might have translated into practice.

"Bird feeding exhibit," Julius Kirschner, December 1931. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 313801; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

Many nature-study texts of the early twentieth century relied on birds to stoke children’s interest in the natural world. Birds, being pretty objects that sang sweet songs, could foster sentimental attachments to nature; they also afforded great opportunities for teaching observation and memorization, since they were so numerous in species, and showed up even in urban areas. I like this exhibit about bird-feeding because it’s so clearly set in an urban milieu. “Use your old Xmas trees for this purpose,” one of the signs planted on the ground advises; I remember doing exactly this as a child in the 1980s.

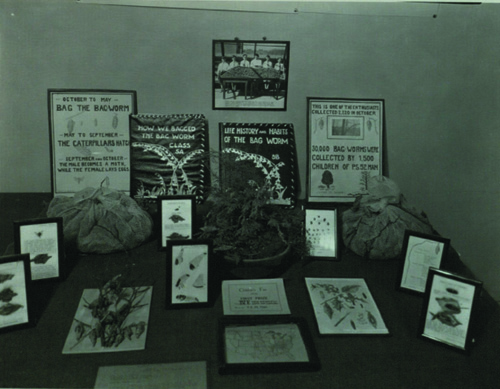

"Life History and Habits of the Bag Worm," Julius Kirschner, December 1930. This exhibit took first place at the fair. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 313416; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

This group exhibit was the result of a project in which kids gathered and destroyed masses of bagworm pupae (click and enlarge to see the photograph of the investigators, featuring a table piled high with soon-to-be-dead bagworm cocoons, at the top of the exhibit). I found some evidence of projects like these carried out by city kids at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum; the focus on destruction of a species may seem strange to modern eyes, used to teaching kids to cherish any bit of nature they can get their hands on, but in the 1930s economic entomology was on the rise, and a project such as this one would have been right in line with adult interests.

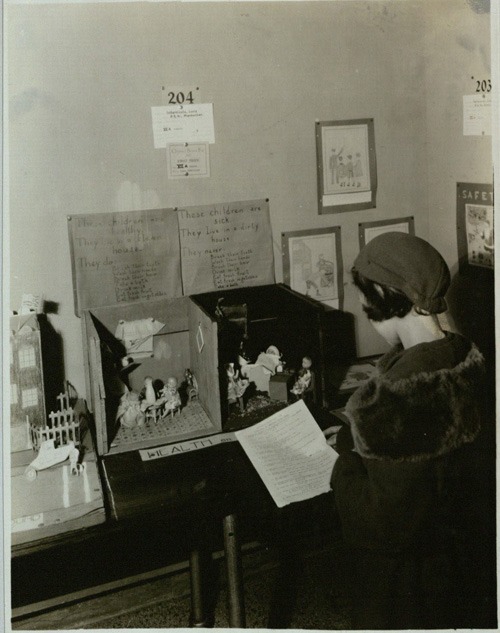

"Health and Cleanliness," "Allen," December 1932. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 314076; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

Here, in a reflection of the judgmental approach adults took toward teaching home sanitation in the Progressive Era, a dollhouse display illustrates the difference between children living in a healthy home and a “dirty” one. Advisable behaviors: brushing teeth, washing hands, brushing hair, drinking milk, eating fresh fruit and vegetables, and taking baths.

"Children's Attitude Toward Public Parks," Julius Kirschner, December 1931. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 311772; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

This exhibit illustrates the “correct attitude” toward public parks: stay on the path, don’t litter. Manners in parks, paths to cleanliness: these projects raise interesting methodological questions common to the fields of childhood studies and children’s history. Are these dioramas “merely” evidence of children parroting their elders’ advice, or are they “really” proof of children’s concerns? Or is the fuzzy dividing line between the two interpretations part of the fun?

"Diving Helmet Made and Submitted by Harry Hanson, Theodore Roosevelt High School, Exhibit from Children's Fair," Julius Kirschner, December 1930. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 313561; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

Proud Harry Hanson! Hopefully his appealing diving helmet made it through the exhibition process without being mauled or stolen; documentation in the AMNH archive suggests that loss of items through exhibition was not uncommon. In 1929, exhibitors lost $23.80 worth of goods, including a “plane” (Norman Plotkin, 1974 East 27th St, Brooklyn), a flashlight (William P. Myhan, 209 West 97th St, NYC), and an aquarium (Philip Neuman, 2854 East 6 St., Brooklyn).

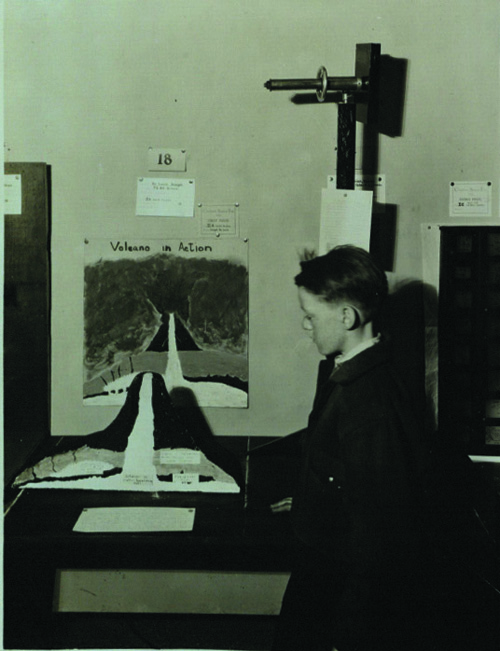

"Volcano in Action," "Allen," December 1932. AMNH Miscellaneous Collection, drawer 94; neg. 314078; American Museum of Natural History Archives.

Some things never change.

penne

Feb 2, 2011 -

1. None of the kids are looking at the camera. 2. I wonder how many times that volcano “experiment” has been carried out. I had always thought mine was the first.

rebecca

Feb 2, 2011 -

1. I know! It’s interesting, right? Same thing as pics of kids in museums – I keep wondering whether they were asked to pose with their interest directed toward the projects. 2. I believe the results of that volcano “experiment” have been independently confirmed. Over. And over. And over. And over. Etc.