Inspired by Adam Golub’s Forbes blog post about choosing holiday books, here’s what I’m packing for this holiday trip northwards and home. As you may be able to tell by the sheer weight of the books listed, we are driving from Texas to Ohio and then to New Hampshire, rather than flying; these volumes will ride more than two thousand miles each way, stashed in the spare-tire compartment of our Volvo.

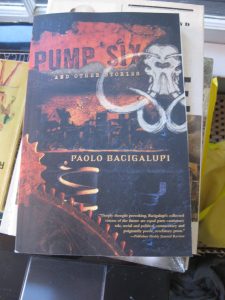

First up, because I already swallowed it whole on the first leg of our ride (the stretch from Texas to Ohio): Pump Six and Other Stories, a collection of short stories by Paolo Bacigalupi. I usually avoid short-story collections, but I loved Bacigalupi’s other books, The Windup Girl and Ship Breaker, so I thought I’d give it a try. I’m glad I did, because each of these pieces is like a little heat-seeking missile aimed straight at my tastes and interests. We’ve got a future dystopia in which medically assisted immortality has led to the criminalization of reproduction (“Pop Squad”); a future dystopia in which a wealthy patron uses extreme surgery to deform servant children so that their bodies can be played like wind instruments (“The Fluted Girl”); a future dystopia in which humans have advanced scientifically to the point where they can regenerate limbs and eat sand (“The People of Sand and Slag”). I read this while sitting shotgun on the long stretches through Arkansas and Tennessee, and at the end of each story I let out a satisfied “Damn!” A poor co-pilot, if a happy reader.

First up, because I already swallowed it whole on the first leg of our ride (the stretch from Texas to Ohio): Pump Six and Other Stories, a collection of short stories by Paolo Bacigalupi. I usually avoid short-story collections, but I loved Bacigalupi’s other books, The Windup Girl and Ship Breaker, so I thought I’d give it a try. I’m glad I did, because each of these pieces is like a little heat-seeking missile aimed straight at my tastes and interests. We’ve got a future dystopia in which medically assisted immortality has led to the criminalization of reproduction (“Pop Squad”); a future dystopia in which a wealthy patron uses extreme surgery to deform servant children so that their bodies can be played like wind instruments (“The Fluted Girl”); a future dystopia in which humans have advanced scientifically to the point where they can regenerate limbs and eat sand (“The People of Sand and Slag”). I read this while sitting shotgun on the long stretches through Arkansas and Tennessee, and at the end of each story I let out a satisfied “Damn!” A poor co-pilot, if a happy reader.

All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery, by Henry Mayer. Every year over the holidays I like to read one book written in, or about, the nineteenth century: last year Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War; two years ago Moby-Dick (definitely best enjoyed lying on one’s side in a book-lined parental library, in front of a roaring fire, eating Chex Mix by the light of the Christmas tree); three years ago Evan Carton’s Patriotic Treason: John Brown and the Soul of America. Something about the austerity of the New England winter seems to bring it out in me. Since I’m not writing about the nineteenth century right now, these books also make me feel liberated from Work and remind me that reading history can be a pleasure activity. This year I’m finally going to read this book about abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, which I bought at Half Price Books in Austin four years ago. I also asked for Mark Twain’s autobiography and Helen Vendler’s Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries for Xmas presents, which may compete with this one for the nineteenth-century slot.

All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery, by Henry Mayer. Every year over the holidays I like to read one book written in, or about, the nineteenth century: last year Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War; two years ago Moby-Dick (definitely best enjoyed lying on one’s side in a book-lined parental library, in front of a roaring fire, eating Chex Mix by the light of the Christmas tree); three years ago Evan Carton’s Patriotic Treason: John Brown and the Soul of America. Something about the austerity of the New England winter seems to bring it out in me. Since I’m not writing about the nineteenth century right now, these books also make me feel liberated from Work and remind me that reading history can be a pleasure activity. This year I’m finally going to read this book about abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, which I bought at Half Price Books in Austin four years ago. I also asked for Mark Twain’s autobiography and Helen Vendler’s Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries for Xmas presents, which may compete with this one for the nineteenth-century slot.

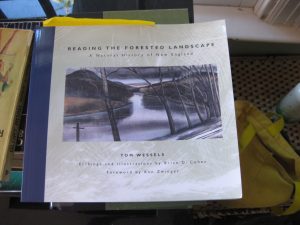

The next three are “duty calls” books. I’m reading them for a class I’m teaching next semester: Nature and American History. First, Wars in the Woods: The Rise of Ecological Forestry in America by Samuel P. Hays (NOT to be confused with War in the Woods: Combating the Marijuana Cartels on America’s Public Lands); second, the fourth edition of Roderick Nash’s classic Wilderness and the American Mind; third, Wessels, Cohen, and Zinger’s Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England. I’m the most excited about that last one. My mom, who walks in the New Hampshire woods every day with our golden retriever Baxter, has had this book for years (in fact, I think I may have given it to her for some Christmas past). Yet somehow I’ve never read it. This is the year I will get to it, and use my own woods walks to apply the knowledge within.

The next three are “duty calls” books. I’m reading them for a class I’m teaching next semester: Nature and American History. First, Wars in the Woods: The Rise of Ecological Forestry in America by Samuel P. Hays (NOT to be confused with War in the Woods: Combating the Marijuana Cartels on America’s Public Lands); second, the fourth edition of Roderick Nash’s classic Wilderness and the American Mind; third, Wessels, Cohen, and Zinger’s Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England. I’m the most excited about that last one. My mom, who walks in the New Hampshire woods every day with our golden retriever Baxter, has had this book for years (in fact, I think I may have given it to her for some Christmas past). Yet somehow I’ve never read it. This is the year I will get to it, and use my own woods walks to apply the knowledge within.

The most ambitious tome in the stack is Melvin Konner’s The Evolution of Childhood: Relationships, Emotion, Mind, which I got out of the UT library cuz it’s still too pricy on Amazon. This book is 900 pages long, and apparently Konner, an anthropologist and neuroscientist at Emory, has been writing it for thirty years. It’s supposed to be a fairly accessible, interdisciplinary survey of the most recent scientific thought on the evolutionary whys and wherefores of childhood behavior. Because the first chapter of my dissertation brought me into contact with people trying to answer the same questions while living in the early 20th century, I think it might be interesting to read this one and see how things have changed; I’m also eyeing it as fodder for some future blog post. We shall see how far I get.

The most ambitious tome in the stack is Melvin Konner’s The Evolution of Childhood: Relationships, Emotion, Mind, which I got out of the UT library cuz it’s still too pricy on Amazon. This book is 900 pages long, and apparently Konner, an anthropologist and neuroscientist at Emory, has been writing it for thirty years. It’s supposed to be a fairly accessible, interdisciplinary survey of the most recent scientific thought on the evolutionary whys and wherefores of childhood behavior. Because the first chapter of my dissertation brought me into contact with people trying to answer the same questions while living in the early 20th century, I think it might be interesting to read this one and see how things have changed; I’m also eyeing it as fodder for some future blog post. We shall see how far I get.

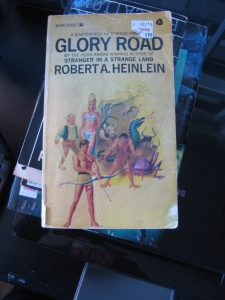

One of the major advantages of being a reader of science fiction is the cheap price, wide availability, and nifty cover art of science fiction paperbacks. I have three or four of these little friends along for this particular vacation ride. First is Glory Road, a Heinlein book from 1964; we’ve got a heroic veteran who retrieves an object said to contain all of the knowledge of humanity inside, and then marries an empress who rules many universes. Wikipedia says this book is more fantasy than sf, and now I’m wondering how much of it I’ll be able to stand; Heinlein’s humor and smarts may get me through it, but I generally avoid the quest narrative at all costs.

One of the major advantages of being a reader of science fiction is the cheap price, wide availability, and nifty cover art of science fiction paperbacks. I have three or four of these little friends along for this particular vacation ride. First is Glory Road, a Heinlein book from 1964; we’ve got a heroic veteran who retrieves an object said to contain all of the knowledge of humanity inside, and then marries an empress who rules many universes. Wikipedia says this book is more fantasy than sf, and now I’m wondering how much of it I’ll be able to stand; Heinlein’s humor and smarts may get me through it, but I generally avoid the quest narrative at all costs.

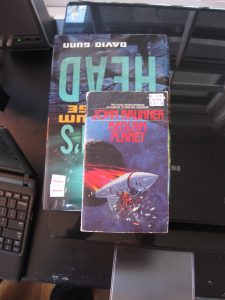

SF pback no. 2: John Brunner’s Bedlam Planet. Love that cover art—the colors are right up my alley. I’ve had a soft spot for Brunner ever since I read The Sheep Look Up, the most devastating enviro-dystopia ever (this is the book that turned me into a GINK). This 1973 novel is about a planet that Earthlings are attempting to terraform—but things are going terribly wrong. “Was there a lot more to planetary ecology than humanity realized?” asks the blurb on the back of the book. I’m hoping for a 70s precursor to the Kim Stanley Robinson Mars trilogy, with a bunch of talk about the ethics of terraforming, mixed with some kind of Solaris-esque sentient planet situation.

SF pback no. 2: John Brunner’s Bedlam Planet. Love that cover art—the colors are right up my alley. I’ve had a soft spot for Brunner ever since I read The Sheep Look Up, the most devastating enviro-dystopia ever (this is the book that turned me into a GINK). This 1973 novel is about a planet that Earthlings are attempting to terraform—but things are going terribly wrong. “Was there a lot more to planetary ecology than humanity realized?” asks the blurb on the back of the book. I’m hoping for a 70s precursor to the Kim Stanley Robinson Mars trilogy, with a bunch of talk about the ethics of terraforming, mixed with some kind of Solaris-esque sentient planet situation.

The final paperback in the bag—for now! I won’t preclude any late-breaking additions—is Higher Education, by Charles Sheffield and Jerry Pournelle. A so-so student joins up with an interplanetary asteroid mining company, and gets his real education on the job. I picked this one up because of its explicit debt to Heinlein’s coming-of-age novels—the “juveniles”, mostly taking space exploration as their milieu, that RAH wrote during the 40s and 50s, and that I’ll be including in the last chapter of my dissertation. I’m about halfway through this one, which seems to share many of RAH’s concerns about the gap between what students learn in school and what’s required in the “real world.” The book also contains lots of disses of the culture of “self-esteem”—which I think is the nineties equivalent of the “life-adjustment” curriculum that RAH scapegoated so much back in the fifties.

The final paperback in the bag—for now! I won’t preclude any late-breaking additions—is Higher Education, by Charles Sheffield and Jerry Pournelle. A so-so student joins up with an interplanetary asteroid mining company, and gets his real education on the job. I picked this one up because of its explicit debt to Heinlein’s coming-of-age novels—the “juveniles”, mostly taking space exploration as their milieu, that RAH wrote during the 40s and 50s, and that I’ll be including in the last chapter of my dissertation. I’m about halfway through this one, which seems to share many of RAH’s concerns about the gap between what students learn in school and what’s required in the “real world.” The book also contains lots of disses of the culture of “self-esteem”—which I think is the nineties equivalent of the “life-adjustment” curriculum that RAH scapegoated so much back in the fifties.

Finally, the guiltiest pleasure of all: Death’s Head: Maximum Offense, by David Gunn. A futuristic supersoldier named Sven Tveskoeg goes on various uber-violent interplanetary adventures; meanwhile, his talking gun cracks wise. Characters in this book are named Indigo Jaxx, Paper Osamu, and, simply, Caliente (that last one is a lady of the night). The author blurb reads as follows: “Smartly dressed, resourceful, and discreet, David Gunn has undertaken assignments in Central America, the Middle East, and Russia (among numerous other places). Coming from a service family, he is happiest when on the move and tends not to stay in one town or city for very long.” How, you might ask, did I come upon this gem? I read The Best Military Science Fiction of the Twentieth Century; Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War; Heinlein’s Starship Troopers; and all of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game books. I decided I wanted to seek out more military SF because I might write some academic essay or other about ideas around youth, technology, and education in the genre. But if I’m honest with myself, I can admit that reading David Gunn is just like watching “The Chronicles of Riddick”: a pleasure not necessarily crafted for thirty-three-year old females like me, but a thing intensely pleasurable nonetheless.

Finally, the guiltiest pleasure of all: Death’s Head: Maximum Offense, by David Gunn. A futuristic supersoldier named Sven Tveskoeg goes on various uber-violent interplanetary adventures; meanwhile, his talking gun cracks wise. Characters in this book are named Indigo Jaxx, Paper Osamu, and, simply, Caliente (that last one is a lady of the night). The author blurb reads as follows: “Smartly dressed, resourceful, and discreet, David Gunn has undertaken assignments in Central America, the Middle East, and Russia (among numerous other places). Coming from a service family, he is happiest when on the move and tends not to stay in one town or city for very long.” How, you might ask, did I come upon this gem? I read The Best Military Science Fiction of the Twentieth Century; Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War; Heinlein’s Starship Troopers; and all of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game books. I decided I wanted to seek out more military SF because I might write some academic essay or other about ideas around youth, technology, and education in the genre. But if I’m honest with myself, I can admit that reading David Gunn is just like watching “The Chronicles of Riddick”: a pleasure not necessarily crafted for thirty-three-year old females like me, but a thing intensely pleasurable nonetheless.

This is the last blog post I’ll be putting up until the second week of January. Happy merriness, everybody.