No, THATCamp did not take place in tents; the Emory Library was kind enough to let us inside. Photo of the headquarters of the Department of Extension at Texas A&M, before the Smith-Lever Act created the Cooperative Agricultural Extension Service in 1914. Photo courtesy of Cushing Memorial Library and Archives.

This past weekend, I went to something called a THATCamp. This surprisingly unsayable handle translates to “The Humanities and Technology Camp.” These “unconferences” on digital humanities topics, which are meant to facilitate maximum info-sharing with a minimum of fuss, hierarchy, and pomp, are open to grad students, professors, archivists, librarians, museum people, programmers, developers, and so on. Sessions are determined collaboratively each morning; some THATCamps, including the one I attended (THATCamp SE), also feature BootCamps, which are more-directed training days for those seeking instruction.

THATCamp is much more relaxed, congenial, and energizing than a regular conference, as this blog post by participant Roger Whitson explains in detail. Not only was I allowed to wear jeans and sneakers, but the “unconference” format means that everybody talks during every session (well, everybody who doesn’t feel like just hanging back and lurking), which means that there are many more points of entry for casual conversation both during and between sessions. I hypothesize that a THATCamp is easier, socially speaking, than a “regular” conference, because the objects of interest are concrete, immediate, and shared. Dating advice holds that you should plan a first date that involves an activity, so that you have something to talk about; THATCamp proves that works for groups as well.

As a person relatively new to the digital humanities, I wanted to go to a THATCamp as an exercise in demystification. I wrote in my application essay that a person freshly interested in the digital humanities can find a lot of information online, and this is all well and good, but there are so many different ways to “do” digital humanities that just reading stuff that you find via Twitter can be overwhelming. Anybody who’s a seasoned digital humanities hand will read this post and see that I only scratched the surface through my THATCamp experience; all of the conversations about coding (which many consider to be the real heart of the unwieldy thing called “digital humanities”—see some discussion about that question here and here) still went right over my head. Because this was my first experience, in some ways I felt like a knowledge leech; as you can see by the list of takeaways below, I got some very specific ideas and tools from the experience, but I wonder how much anybody else got from my own contributions. Hopefully next time (and there will be a next time!) things will be different.

A few of those concrete takeaways:

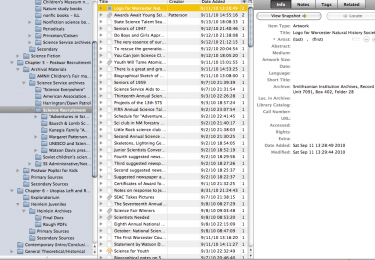

a) I was pretty excited about the session on Research Hacks that Miriam Posner proposed, having evolved my own method of dealing with archive photos and then having gotten an idea, via this post on ProfHacker, that my way may be positively creaky and unrefined compared to some. My pre-THATCamp method of archiving: take a bunch of pics at the archive during the day, inserting them into desktop folders labeled with the correct box and folder number. Return home, go through each folder, turn each jpeg into a PDF (using Preview), combine PDFs (using the open source program PDF Split and Merge). Enter each item into Zotero, inserting the appropriate metadata, and then attach the PDF to the Zotero record, renaming the PDF using the parent metadata. I joked at this session that this process was only made tolerable by the fact that I watched all four seasons of “Battlestar Galactica” while doing this data entry task on one archive trip; if you look at the size of the library below, you can see why I needed the distraction (the other major archive I raided took me all the way through “Mad Men” seasons one and two):

Well! Come to find out, there’s a tool on the Mac called Automator that can save me the first two steps of that long, drawn-out process. As Miriam details in this blog post, you can order Automator to do a succession of things to your batch of archive pics, including turning your jpegs into PDFs, combining, and even OCRing (a step I haven’t tried to tackle with my sources, as of yet). Better late than never, I guess…

b) Timelines, timelines, timelines. Brian Croxall ran a BootCamp session about a method he evolved for making a timeline out of a GoogleDoc spreadsheet, using some scripts written by a group at MIT called the Simile Project (SIMILE: “Semantic Interoperability of Metadata and Information in unLike Environments”). This kind of timeline would work well to use with a class, because you could have students input events independently, asking them to do the work of identifying what events are relevant to your topic of discussion, and why; seeing their choices visually juxtaposed with the choices of their classmates would be helpful.

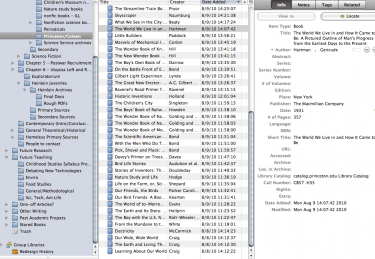

I also found out that Zotero has a “Timeline” function, which also uses the scripts that SIMILE wrote. This can make a Zotero library that looks like this (publication dates of each book are hidden, unless you click on their records):

Into an interactive page that looks like this:

c) Omeka. I had heard of this CMS (Content Management System—more demystification) before, and vaguely thought I might use it for some purpose or another, but the BootCamp session on its features was extremely helpful. This session took place at the end of a day in which we had been working with Civil War letters that will eventually be part of an Emory project cataloging letters in their collection, so we were allowed inside this project’s Omeka dashboard to play around. Future projects I might do with Omeka: make exhibit of the set of beautiful 1970s-era educational flashcards my teacher friend gave me a couple of years ago; make exhibit of family objects when I help my mom clean out our basement this summer; make exhibit of encyclopedia entries from kids’ encyclopedias (this would allow me to cross-reference by subject and year while writing my chapter 3 about non-fiction kids’ books). Future teaching with Omeka: for a childhood studies class, I’d like to ask students to create an archive of objects from their own childhoods, with historical context and analysis attached to each record.

I only worry that Omeka will prove all too attractive to my digital packrat tendencies, and wonder whether I will start sinking way too much time into my scanner; how, as a later discussion session asked, can I get “credit” for this kind of work?

d) Bits and Bobs. One session on Saturday, Your Favorite Application, was a simple show-and-tell. I lurked for this one, knowing that most of the applications I use are pretty common (“Um, I really like this thing called…ITunes?”) Major finds for me here: SelfControl (app that shuts off the distracting parts of the Internet while you’re supposed to be writing; unlike MacFreedom, this program forbids Internet even if you uninstall it!); 1Password (for keeping all passwords together, and generating stronger passwords); ReadItLater (like Instapaper, marks things on the Internet as “to-read”; also downloads the actual text of the article, so that you can save the things you stunble upon and look at them later even if you’re on your phone and out of data coverage).

Many thanks to THATCamp Central at the Center for History and New Media, as well as the Mellon and Kress Foundations, for the BootCamp fellowship that made it possible for me to attend this unconference. I highly recommend everybody check the list of upcoming THATCamps, apply for a fellowship, and attend.