I just wound up three weeks doing research at the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton, looking at a trove of books about science and industry from the 1920s and 1930s. (Thank you, Friends of the Princeton University Library, for your support.) I thought I might post a version of the brown-bag talk I gave to the Friends of the Library, which gave a more comprehensive overview of the books I saw, but I am, once again, thwarted by copyright (the talk includes a ton of images, some of which are a decade too young to be in the public domain).

So I thought I might instead show off my favorite find, which happens to have been published in 1921: Henry Chase Hill’s wild encyclopedia The Wonder Book of Knowledge, ambitiously subtitled “The Marvels of Modern Industry and Invention, the Interesting Stories of Common Things, the Mysterious Processes of Nature Simply Explained,” and boasting 700 illustrations.

The preface to this volume was careful to note that the book could have appeal to audiences beyond children, citing “average workmen” as another potential readership. I find it fascinating to note how these two audiences often get mashed together by people writing popular scientific books during this time. The inscription in this copy seems to indicate a young owner.

Books like these assumed the existence of a complicated modern world, full of processes that the ordinary citizen/child might find fascinating but alien. (“Most of us realize that we live in a world of wonders and we recognize progress in industries with which we come into personal contact, but the daily routine of our lives is ordinarily so restricted by circumstances that many of us fail to follow works which do not come within our own experience or see beyond the horizon of our own specific paths,” Hill writes.) But—rescue!—this complex world could also be explicable between the covers of a single volume. The table of contents of the Wonder Book of Knowledge promises answers to a wild ball of questions tangled together, interspersed with longer “Stories” of various objects and industries.

In his Preface, Hill refers to “the constant avalanche of questions suggested by the growing mind”; echoing this metaphor, the questions and answers in the Wonder Book are presented devoid of any connection, as if rising up from a stream of consciousness: “What kind of dogs are prairie dogs?”; “What is spontaneous combustion?”; “How does an artesian well keep up its supply of water?”; “Where do dates come from?” One of the themes I’ll be addressing in my dissertation is the way that people in the first half of the 20th c started directing admiration and excitement toward childish curiosity—prizing it and seeking to develop it, rather than, as they might in another era, seeing it as intrusive or insolent. Lists of questions like these offer some indication as to the parameters of approved subjects for this curiosity.

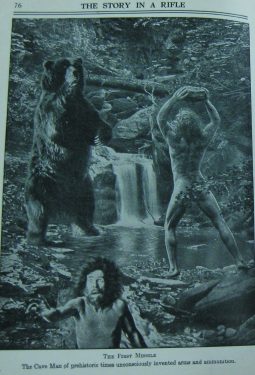

This sequence of photo-illustrations, from “The Story in a Rifle,” displays the fascination with prehistoric man familiar to many of the “Story Of” books of this era. In this particular “Story,” weapons are discovered when a caveman lifts a rock to scare off a bear; his terrified friend, Craven Caveman, runs the other way:

Later in the evolution of the rifle, a Daniel Boone type desperately loads his weapon as a herd of ungulates approaches:

Photo-illustrations decorate many of these Stories (indeed, I found this book through Mus White’s wonderful bibliography of photographically illustrated children’s books), but the “Story of a Rifle” illustrations are notable for their unusual verve and vigor. More commonly, the photos were donated by the industries under examination, and are fairly unengaging. At my brown bag talk, we discussed the extreme basic-ness of many of these photos, all the more striking for its contrast with the excitement that the authors professed about them (examples would be William Clayton Pryor’s “Photographic Story-Books” of industry, with photos that were, in many cases, murky and uninteresting). We speculated that this was the equivalent of the present-day hype over anything “social media,” which seems to assume that the inherent fascination with the medium would trump any weakness of actual form or content.

The Wonder Book of Knowledge is unrelentingly positive about American industry, emphasizing a theme of abundance and possibility; thus, in “The Story of the Telephone,” the American telephone system is so superior that our hotels have better infrastructure than whole foreign cities.

Even in the “Story of Sausage,” the author discourses at length on the cleanliness of the packing houses, offering—perhaps self-consciously?—a picture quite at odds with the grisly scenes depicted in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle just fourteen years earlier: “The standard of cleanliness in the sausage kitchen has to be unusually high. Whenever white tile is not possible, white paint is used in profusion. The shining metal tables and trucks, on which the product is handled, give a new confidence in sausage.”

As with many of my primary sources, I’ve got some kind of primal affection for this book; it’s something I would have loved to have read at age eight. Now I’ve got to figure out a way to write about it.