At Lowe’s the other day, I stumbled upon these books of wallpaper samples for boys’ and girls’ rooms. Having spent the past three weeks talking in my class about the recently hardened pink-and-blue dichotomy reigning in the world of children’s clothing and toys (for more on this, see Peggy Orenstein’s book Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from the Front Line of the New Girlie-Girl Culture, or Jo Paoletti’s upcoming Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America), I couldn’t resist exploring these, while taking some (admittedly terrible) cell phone pictures.

I wasn’t surprised to see that the categories of wallpaper offered for each gender reflected the same division between aesthetics and action that Orenstein noted when she visited a toy convention for her book. Boys’ wallpaper is movement-oriented: “Out of This World,” “Sea Breeze,” “Action Packed,” “Go Team Go,” and “Cars” (that’d be the Disney/Pixar Cars). Girls’ walls are all about pretty: “In Full Bloom” (flowers), “Dare to Have Flare,” “Everything Nice,” and the inevitable Disney Princesses. (I also found out from this expedition into kids’ wallpaper that Disney now sells Disney Fairies, bundled together in the same way as the Princesses. Here is the website. It’s happening.)

As somebody interested in the way that science and nature get represented to children, I lingered the longest on these two contrasting ocean offerings.

How can it be that each represents—in some tangential way—the same actual underwater world?

I would have been terrified to have the boys’ ocean on my wall as a child, but I don’t think that’s because I’m a girl. I found sharks amazing and awful; in an episode famous in family lore, my sister once chased me around the house with a National Geographic, opening it to a picture of a great white surfacing, as I shrieked and shrieked.

The boy-ocean, per allen + roth, is full of challenges, drama, and teeth. Although it looks more like the actual ocean than the girl-ocean—at least it’s brown and blue—it’s still Disney-fied, giving the impression that the undersea world is charismatic and bloody; the frame is literally full of characters. Sharks have never achieved exactly the same status as dinosaurs in kids’ culture, but they have many of the same attributes: powerful, scary, bizarre, living in a world very far from our own. This wallpaper seems almost to issue a challenge to a boy: can you swim with the sharks, day after day? Wouldn’t you be scared to wake up at night and see their teeth shining in the glow of your nightlight?

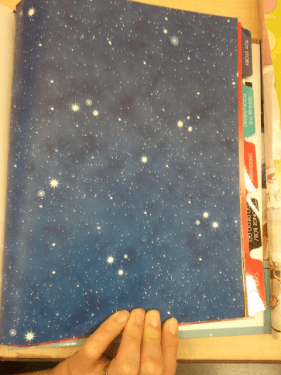

I much prefer the sky wallpaper included in the “space” section of the boys’ book; although an entire room papered in this might provoke feelings of existential angst, that might be better than the fight-or-flight instinct those sharks provoke.

The girl-ocean, on the other hand, looks like a jewel-box, filled with friendly pastel accessories. Again, there is no action, only decoration. This is unrealism of a different stripe. While the boy-ocean makes the false promise of endless startlement, this wallpaper gives the impression that all parts of nature can be reinterpreted through a pink lens, and can be pleasing insofar as they are pretty.

Perhaps the two oceans are simply an extension of an old division; surely 1910s girls were encouraged to study botany, while 1910s boys read Ernest Thompson Seton on wolves. My students and I have been trying hard to avoid the alarmist “kids’ culture these days is degraded” approach to analysis. But there’s something about the immersive nature of these two visions, and the pinkness of the girl-ocean, that seems new to me, and—I’ll say it—unwelcome.

Laura Vivanco

Nov 10, 2011 -

It occurred to me that this looks a bit like a version of the kind of seascape that would be thought suitable for a Little Mermaid.

I recently saw a poster for Shark Night 3D and something about it made me wonder if heterosexual men are supposed to identify with the shark in some way. Then I read a synopsis and if that synopsis is correct, it seems as though in the plot there really is a connection between the sharks and a man’s anger at a woman. Obviously there’s a difference between that poster and the wallpaper you saw, but it does make me wonder if sharks are seen to embody certain characteristics which are considered masculine. Ah, here’s another example I just found. Bryan S. Ghingold’s arguing that in Jaws the “The shark’s designation as “über-male” is seen throughout the film. In addition to its size, which has been exaggerated to the brink of caricature, it is the most phallic representation in the film. The shark’s body is itself phallic, and at its head is a frightening and domineering power, represented by its mouth.” I haven’t seen that film either, so again I’m dependent on someone else’s comments about the film, but it does seem that I’m not the only one to consider the possibility that sharks might be associated with masculinity.

Rebecca Onion

Nov 11, 2011 -

It’s definitely true that there’s something gendered about the shark in shark movies; I’d point to just the way that every shark movie since Jaws seems to have had a promo poster that features the shark rising up out of the deep and threatening a female bather. The underwater shot of the woman’s legs is another common feature; this has been repeated so many times in so many shark movies that it can appear almost comic, and I’ve seen shark movies in which the audience is meant to laugh at the woman’s surprise when the shark “gets” her (shark=trickster figure). I also think it’s really interesting that the article you linked to articulates this strange connection between the power of the shark and the lack of power of the male protagonists. It reminds me of the way that some protagonists in HP Lovecraft stories begrudgingly admire, and sometimes even up assisting or serving, the terrible and unthinkable threats that they encounter.